Grief is not a problem to be solved.

It is not a phase to complete.

It is not a set of emotions to process and then move beyond.

Grief is an encounter.

An encounter with absence.

An encounter with love that no longer has a place to land.

An encounter with the terrifying truth that life does not ask our permission before it changes us.

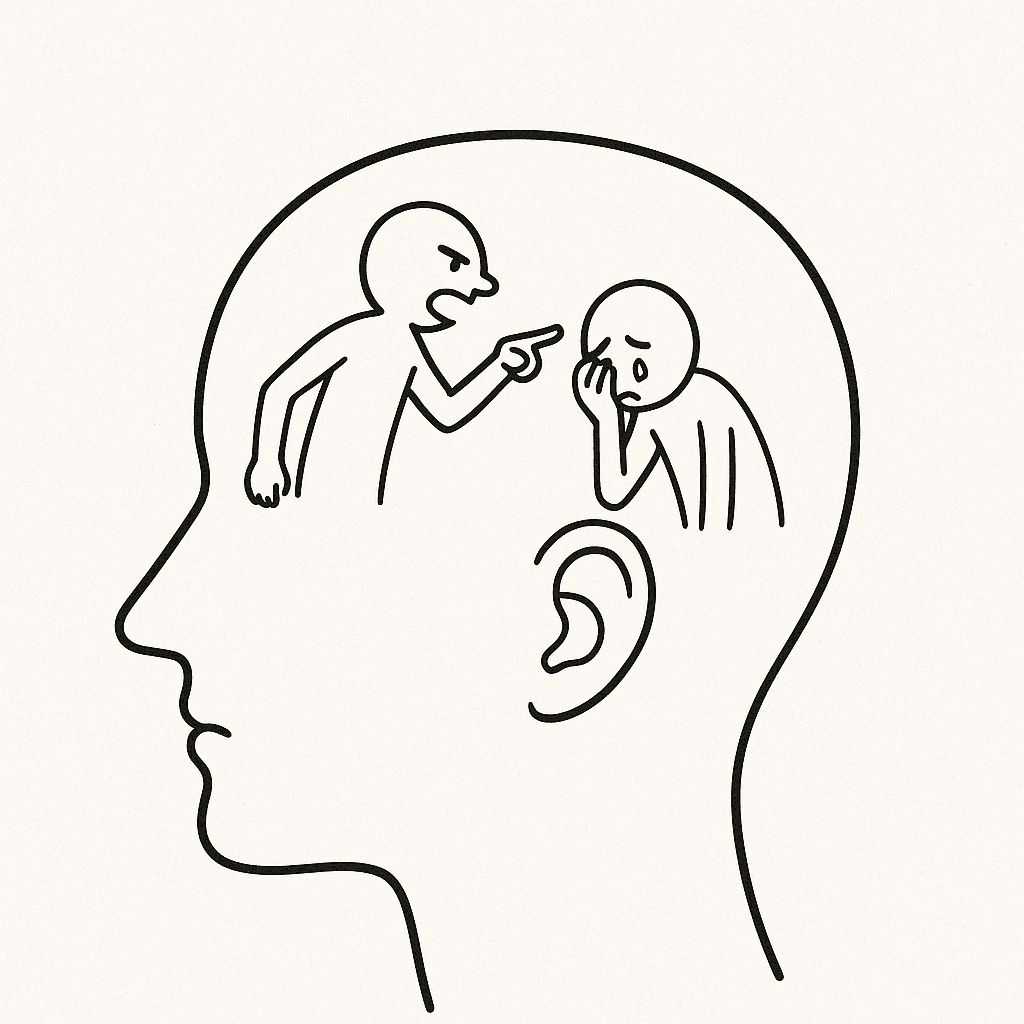

Most people come to grief wanting relief. That is understandable. Pain begs for an exit. But grief does not respond well to force. It does not loosen its grip when commanded. In fact, the more urgently we attempt to escape it, the more it insists on being known.

What follows are five exercises. Not techniques. Not coping strategies. Exercises in the truest sense: ways of entering grief rather than managing it. Each one is grounded in existential thought, person-centered care, and the belief that healing does not come from fixing what is broken, but from allowing what is real to speak.

These exercises are meant to be done slowly. Over weeks. Over months. Some may return again and again throughout a lifetime. There is no expectation of completion. Only contact.

Exercise One: The Chair of the Absent

There is a particular cruelty in grief that is rarely acknowledged: the world keeps its furniture even when the person is gone.

Their chair remains.

Their mug waits in the cupboard.

Their side of the bed does not protest its emptiness.

This exercise begins there.

Place an empty chair in front of you. Do not imagine the person sitting in it yet. First, notice the chair itself. Its shape. Its weight. Its stillness. Allow your body to register the reality of absence before your mind tries to fill it.

Then, gently, allow the person you have lost to arrive in your imagination. Not as a ghost. Not as a memory collage. Simply as them. As they would be if they were still alive and capable of listening.

Now speak.

Do not edit yourself.

Do not speak well.

Do not try to be fair.

Say what was left unsaid.

Say what feels selfish.

Say what feels ungrateful.

Say what you are ashamed to still want.

Grief is not polite. Love unfinished rarely is.

At some point, stop speaking. Sit in the silence. Notice what happens in your body. The tightness. The release. The trembling. The heat behind the eyes. This is not emotional catharsis for its own sake. This is contact with reality as it is now.

When you are ready, speak again. This time, allow yourself to answer. You are not the person you lost, you are yourself, responding to what you just said. Often, something surprising emerges here: compassion for the self who survived.

This exercise honors a central truth of grief: relationships do not end when people die. They change form. And unspoken truths do not dissolve simply because there is no longer a body to hear them.

Exercise Two: The Map of the Self Before and After

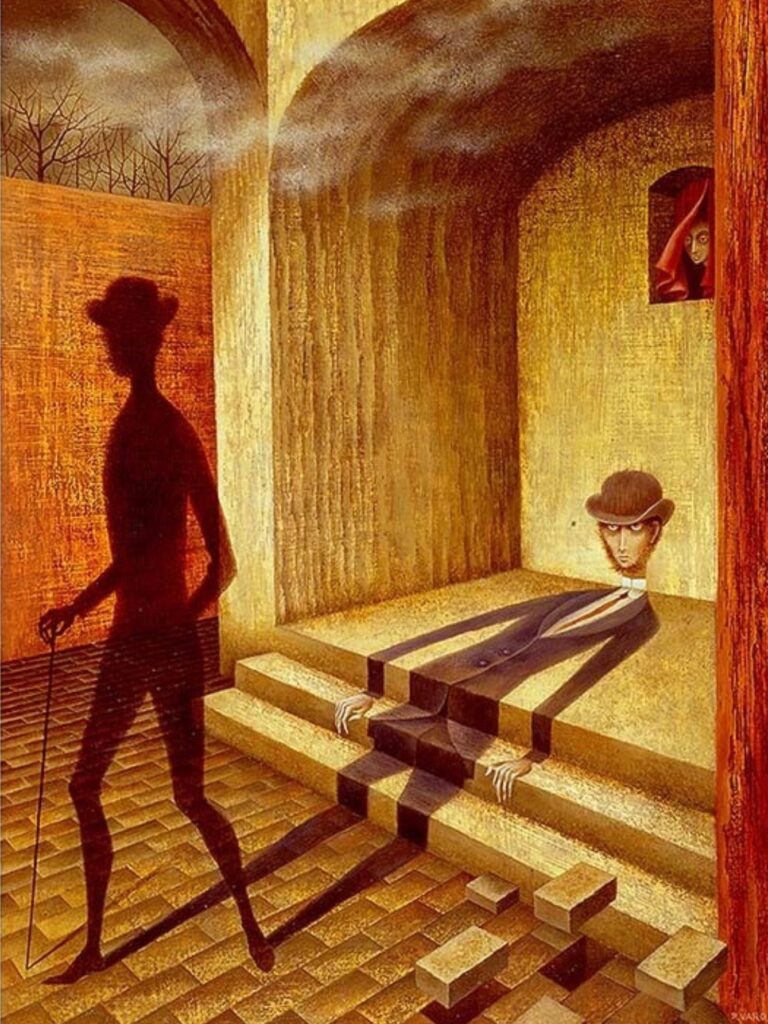

Loss does not only take people. It takes versions of us.

There is the self who existed before. The one who believed certain things were guaranteed. The one who assumed continuity. The one who had not yet learned this particular kind of pain.

And then there is the self who exists after. Perhaps a wiser self, but also more fragile, more cautious, more aware of the cost of loving deeply.

This exercise invites you to meet both.

Take a blank page. Divide it down the middle.

On the left, write: Who I Was Before the Loss

On the right, write: Who I Am Now

Do not aim for completeness. Aim for honesty.

What did the earlier self believe about safety?

About fairness?

About time?

What did they assume would never happen?

Now turn to the right side.

What do you know now that you wish you didn’t?

What have you lost beyond the person (innocence, trust, ease, certainty)?

What have you gained that feels complicated to admit (depth, clarity, courage, tenderness)?

Most people are tempted to turn this into a redemption story. Resist that urge. This is not about silver linings. It is about truth.

Sit with the tension between these two selves. Neither is wrong. Neither can be returned to. Grief lives in that space between who we were and who we must now learn to be.

If you wish, write a letter from one self to the other. Let the earlier self grieve what they did not know. Let the current self mourn what they can never again be.

This exercise acknowledges a difficult existential reality: loss permanently alters identity. Healing is not a return. It is a reorientation.

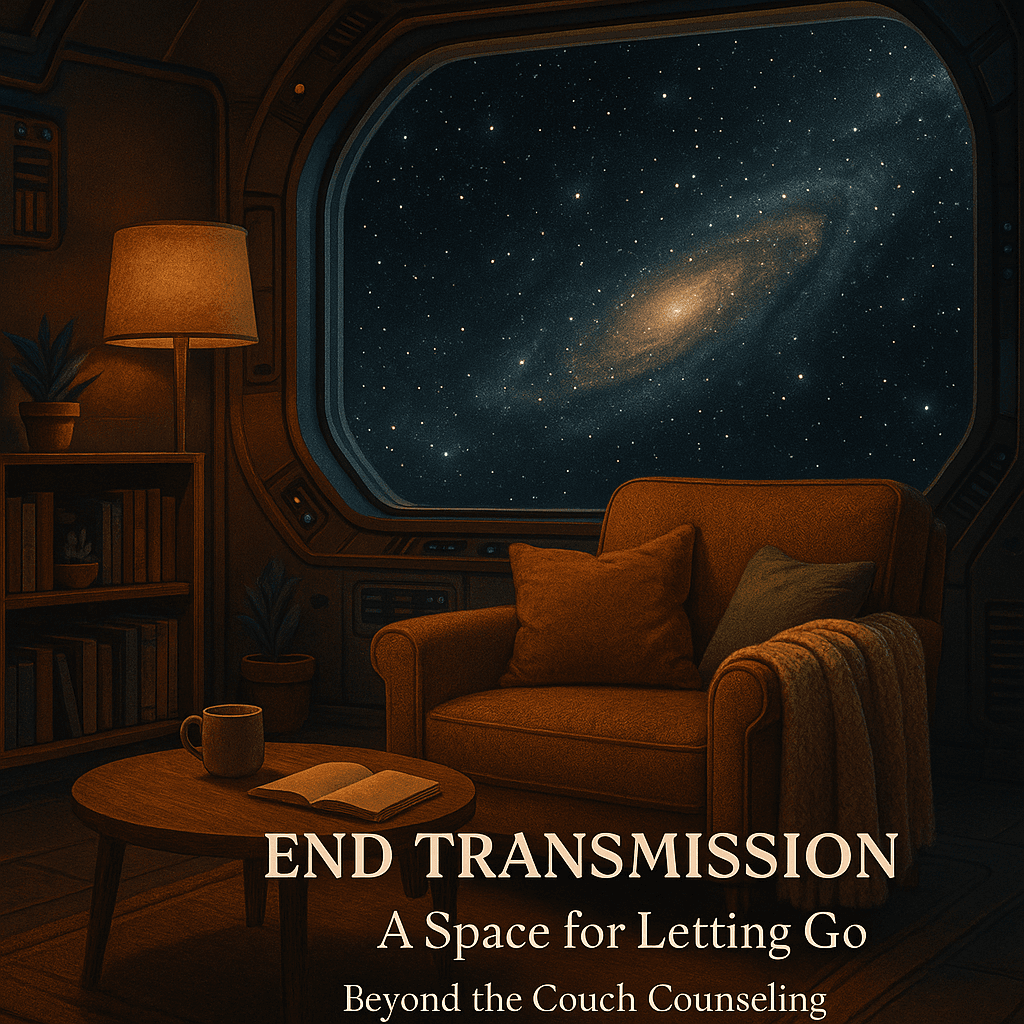

Exercise Three: The Night Watch

Grief has a circadian rhythm.

It waits until the house is quiet.

Until the distractions have gone to sleep.

Until there is no one left to perform wellness for.

This exercise is designed for those moments.

Choose a time when you are alone and uninterrupted. Dim the lights. Sit or lie down comfortably. Place one hand on your chest or abdomen. Feel the simple fact of breath entering and leaving.

Now, instead of trying to calm yourself, ask a question inwardly:

What does my grief need me to know right now?

Do not answer immediately. Let the question hover.

Images may arise. Sensations. Memories. Or nothing at all. Whatever comes is enough. Your task is not to interpret or fix. It is to witness.

If emotions intensify, stay with them as long as you can without overwhelming yourself. Name them quietly if that helps. Sadness. Rage. Longing. Fear. There is no hierarchy here.

This exercise is rooted in the belief that grief is communication. When listened to with patience, it often reveals needs that have been ignored: rest, expression, connection, meaning.

End the practice by thanking yourself for staying present.

Exercise Four: The Conversation with Mortality

Most people try to grieve without acknowledging the deeper terror beneath it: that loss exposes our own finitude.

We mourn not only the person, but the illusion that life is stable.

This exercise asks you to face that truth directly.

Write the following question at the top of a page:

Knowing that everything ends, how do I want to live now?

This is not a motivational prompt. It is an existential inquiry. Take…… your……. time.

Consider what no longer feels worth postponing.

What feels unbearably precious.

What relationships matter differently now.

Grief often strips life of trivialities. What remains is not always comfortable, but it is usually honest.

Notice if fear arises as you write. Fear of wasting time. Fear of choosing wrong. Fear of loving again. These fears are reminders that you are taking life seriously.

There is no correct answer to this question. There is only the act of asking it in the presence of loss.

This exercise honors grief as a teacher, not because it is kind, but because it is clarifying.

Exercise Five: The Act of Carrying Forward

Grief asks an impossible question: How do I continue to love someone who is no longer here?

The answer is not forgetting.

It is not “moving on.”

It is integration.

Choose one quality of the person you lost. Not an achievement. A way of being. Kindness. Humor. Fierceness. Curiosity. Gentleness.

Ask yourself: How can this live through me now?

This is not about becoming them. It is about allowing love to remain active rather than frozen in longing.

Perhaps you practice their generosity with others.

Perhaps you adopt their courage in moments of fear.

Perhaps you speak their name more freely.

This act does not diminish your grief. It dignifies it.

Grief does not end when pain fades. It transforms when love finds motion again.

A Closing Reflection

Grief does not ask us to be strong.

It asks us to be honest.

These exercises are not meant to take your pain away. They are meant to help you suffer truthfully, without abandonment of the self.

If you find yourself undone by this work, that does not mean you are failing. It means you are allowing something real to touch you.

At Beyond the Couch Counseling, we believe grief deserves space, patience, and reverence. Not pathologizing. Not rushing. Not fixing.

If you need someone to sit with you while you do this work, you do not have to do it alone.

And if all you did today was read this and feel something stir, that is already enough.

Love does not disappear.

It changes shape.

And sometimes, it teaches us how to live more honestly than we ever did before.